Cuma in-depth

Cuma in-depth

Cuma – In-depth

The lake Averno

In Cuma, according to tradition, the access, originally located by the sea, near a spring thought to be of the Styx river, was at Averno lake. The hellish landscape was completed by the Acherusia swamp, the present Fusaro lake. Over time, the location of the gates of Hades has changed: nevertheless, in Book VI of the Aeneid the figure of the Sibyl and the cult of Apollo seem linked to mount Cuma, on whose slopes Aeneas meets the prophetess,

Palace Giant

The famous Palace Giant was found in the seventeenth century and exhibited in 1668 by Don Pedro Antonio d’Aragona near the Royal Palace in Naples. It is a large bust of Jupiter, originally a seated statue of the god, bearded and with a flowing hair, covered by a cloak resting on his shoulders. For the Neapolitans the sculpture was for a long time the symbol of dissent, rebellion and provocation, what the so-called “Pasquino” was for Rome and the “Gobbo of Rialto” for Venice: indeed, it collected anonymous complaints and mocking messages that people left near the statue, chosen for its voice. In 1809, the Giant, after having suffered numerous damages and restorations, was brought to the Royal Stables, and then entered permanently at the Reale Museo Borbonico of Naples, current National Archaeological Museum.

Greek colonization of the West

The colonization was a vast migratory phenomenon that affected Sicily and southern Italy from the eighth century B.C. It was a massive movement of people caused by the crisis of the Greek societies of origin, due to the increase of population, to famine, to concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few. Within about two centuries all the coasts of southern Italy were controlled by Greek cities. But if today the concept of colony inevitably implies that of political dependence, at that time things were very different: the group of citizens who went to found a new city became a autonomous, member of a new independent community over which the motherland had no authority.

Lake of Licola

This inner basin, now disappeared and originally communicating with the open sea, provided a landing place from the first moments of life of the settlement and became gradually the city port. The first Greeks then settled in a lagoon situation, with large swamped areas, to the point that in the last quarter of the eighth century there was already a first reclamation. The lake was affected by an ambitious project of the Emperor Nero, who wanted to create a canal along 160 miles to connect the Phlegraean area, and in particular Pozzuoli, with Rome, creating a subsidiary route to the sea coastal navigation. This fossa navigabilis would have exploited lakes and coastal swamps (lakes of Licola and Patria, swamps of Sessa Aurunca and Fondi, the lake basins of the Lazio coast up to the lagoons of Ostia) and was to constitute the backbone of a vast project to clean up the coastal plain. The death of Nero determined the abandonment of the work.

(Naples, Museum of Capodimonte)

Battle of Aricia

According to tradition in 509 B.C. Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of the Tarquini dynasty, was driven out of Rome, where the republic was established and, since then, the power entrusted to two consuls. Soon after the powerful Etruscan king of Chiusi, Lars Porsenna, ally of Tarquinius, attacked the young republic. The strenuous defense of the Romans convinced Porsenna to make peace. Meanwhile, the Latins, taking advantage of the moment of difficulty, had detached themselves from Rome and had offered refuge to Tarquinius. For this reason Porsenna opened hostilities against them: the clash took place near Aricia, in the Alban Hills, where the Etruscan army, led by Arunte son of Porsenna, was badly defeated also thanks to the help of the Cumans led by Aristodemo.

Samnite temple

This building, with risers in tuff and terracotta roofs decorated and painted in the Italic way, presented a beutiful doric frieze with beautiful painted metopes, exposed to the Museum of Baia, which constitute a unique architectural decoration of central southern Italy and a rare example of late-classical non-funerary painting.

Agrippa

From the 1930s BC, the general Agrippa used the numerous landing places of the Phlegraean area to accommodate the fleet, partially converting to a military use non only the commercial ports of the colony of Puteoli, but also the interior basins that had made the fortune of ancient Cuma, and completing them with the new structures of the so-called Portus Iulius. These great maritime achievements were accompanied by impressive engineering works, such as the series of tunnels that connected the Phlegraean lakes, transformed into inland docks to facilitate the supply of ports and the rapid movement of troops.

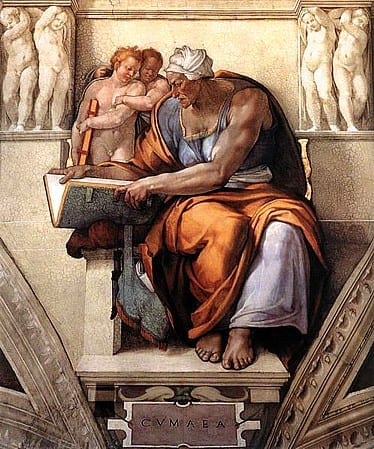

sibyl

According to tradition, the Sibyl was a divine and human creature at the same time, chosen by God as a spokesman to communicate his responses: her usual image is that of a prophetic priestess in a state of inspiration. From the ancient authors we know her dark story: the god Apollo had granted her immortality, but not eternal youth. So she grew older, becoming smaller and thinner, until only her voice remained. Her responses remained written, in Greek, in the Sibylline books, so precious to the Romans that they were preserved first in the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and then, with Augustus, in the temple of Apollo. The figure of the Cuman Sibyl was consecrated by an illustrious historical tradition that, born in the Greek world, crossed the Roman world and Christianity, continuing the humanistic and Renaissance literary and artistic production (for example in Petrarch, Boccaccio, Marsilio Ficino, Michelangelo).

(Florence, Uffizi Gallery)

(Rome, Sistine Chapel)

Previous

Next