Cuma

Cuma

THE DISCOVERY

The first reports of archaeological discoveries in Cuma date back to the beginning of the seventeenth century, but the excavations, wanted by Prince Leopold of Syracuse, brother of King Ferdinand II began only from the middle of the nineteenth century. After the unification of Italy, the English archaeologist Enrico Stevens investigated the tombs, while the Savoy promoted the excavations on the Acropolis. Researches into the lower terrace and on the lower city then followed, thank to the far-sighted expropriation by the state of land of archaeological interest. Since the nineties of the twentieth century the city has been the subject of systematic surveys by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, who invited Italian and foreign universities and research institutions of the city of Naples to participate in the works led in the area of the Amphitheatre, the walls, the Forum and its public buildings, as well as in the lower town and in the Roman necropolis along via Domiziana, which goes towards Licola.HISTORY AND MONUMENTS

The first indigenous settlements of Cuma are on the acropolis and date back to the end of the ninth-first half of the eighth century B.C. The city was the oldest Greek colony in the West, founded by groups from the cities of Chalcis and Eretria, who at the same time had also settled in the island of Ischia (Pithekoussai the Greek name): as shown by the first Greek tombs, the colonization must have taken place in the second half of the eighth century B.C., in accordance with the traditional foundation date handed down from ancient literary sources (730 B.C.). Since the beginning the plain was occupied where later, from the IV sec. a.c., the lower city would have risen, overlooking the lake of Licola. The cliff of the acropolis dominates the plain, allowing the control of a vast stretch of coast, from Miseno to Circeo.Approfondimenti

Informazioni aggiuntiveLa città è strettamente legata al racconto del mitico viaggio di Enea, cantato da Virgilio nell’Eneide, come punto di arrivo dell’eroe troiano sulle coste laziali.

Secondo la tradizione ripresa da Virgilio, infatti, appena sbarcato Enea fece il primo sacrificio, in un luogo presso il fiume Numico (oggi Fosso di Pratica: Numico_1), dove poi sarebbe sorto un santuario dedicato a Sol Indiges. Inseguendo una scrofa bianca gravida, l’eroe percorse una distanza di 24 stadi: qui la scrofa partorì trenta piccoli e il prodigio offrì ad Enea un segno della volontà degli dei di fermarsi e fondare una nuova città. L’eroe incontrò Latino, il re della locale popolazione degli Aborigeni, il quale, dopo aver consultato un oracolo, capì che i nuovi arrivati non dovevano essere considerati degli invasori, ma come uomini amici da accogliere. Enea sposò dunque la figlia di Latino, Lavinia, e fondò la città di Lavinium, celebrando la nascita di un nuovo popolo, nato dalla fusione tra Troiani e Aborigeni: il popolo dei Latini. Il mito racconta che Enea non morì, ma scomparve in modo prodigioso tra le acque del fiume Numico e da questo evento fu onorato come Padre Indiges: Il padre capostipite.

La piazza pubblica della città aveva una pianta rettangolare, ornata sui lati lunghi da portici, su cui si aprivano diversi edifici: uno di questi aveva forse la funzione di “Augusteo”, luogo dedicato al culto imperiale, come sembra indicare il ritrovamento di splendidi ritratti degli imperatori Augusto, Tiberio e Claudio. Sul lato corto occidentale si affacciavano un edificio elevato su un podio, forse la Curia (luogo di riunione del governo locale), e un tempio, risalente ad età repubblicana.

La piazza pubblica della città aveva una pianta rettangolare, ornata sui lati lunghi da portici, su cui si aprivano diversi edifici: uno di questi aveva forse la funzione di “Augusteo”, luogo dedicato al culto imperiale, come sembra indicare il ritrovamento di splendidi ritratti degli imperatori Augusto, Tiberio e Claudio. Sul lato corto occidentale si affacciavano un edificio elevato su un podio, forse la Curia (luogo di riunione del governo locale), e un tempio, risalente ad età repubblicana.

Il santuario, situato ad est della città antica, era dedicato alla dea Minerva, che a Lavinium è dea guerriera, ma anche protettrice dei matrimoni e delle nascite. È stato trovato un enorme scarico di materiale votivo databile tra la fine del VII e gli inizi del III sec. a.C., costituito soprattutto da numerose statue in terracotta raffiguranti soprattutto offerenti, sia maschili che femminili, alcune a grandezza naturale, che donano alla divinità melograni, conigli, colombe, uova e soprattutto giocattoli: le offerte simboleggiano l’abbandono della fanciullezza e il passaggio all’età adulta attraverso il matrimonio

Eccezionale il ritrovamento di una statua della dea, armata di spada, elmo e scudo e affiancata da un Tritone, essere metà umano e metà pesce: questo elemento permettere di riconoscere nella raffigurazione la Minerva Tritonia venerata anche in Grecia, in Beozia, e ricordata da Viirgilio nell’Eneide (XI, 483): “armipotens, praeses belli, Tritonia virgo” (O dea della guerra, potente nelle armi, o vergine tritonia…)

Eccezionale il ritrovamento di una statua della dea, armata di spada, elmo e scudo e affiancata da un Tritone, essere metà umano e metà pesce: questo elemento permettere di riconoscere nella raffigurazione la Minerva Tritonia venerata anche in Grecia, in Beozia, e ricordata da Viirgilio nell’Eneide (XI, 483): “armipotens, praeses belli, Tritonia virgo” (O dea della guerra, potente nelle armi, o vergine tritonia…)

Il culto del santuario meridionale nasce in età arcaica ed era caratterizzato da libagioni. Nella fase finale il culto si trasforma invece verso la richiesta di salute e guarigione, documentato dalle numerose offerte di ex voto anatomici. Sono state trovate iscrizioni di dedica che ricordano

Castore e Polluce (i Dioscuri) e la dea Cerere. La molteplicità degli altari e delle dediche è stata interpretata come testimonianza del carattere federale del culto, quindi legato al popolo latino nel suo insieme: ogni altare potrebbe forse rappresentare una delle città latine aderenti alla Lega Latina, confederazione che riuniva molte città del Latium Vetus, alleatesi per contrastare il predominio di Roma.

Dionigi di Alicarnasso, vissuto sotto il principato di Augusto, afferma di aver visto in questo luogo, ancora al suo tempo, nel I sec. a.C., due altari, il tempio dove erano stati posti gli dèi Penati portati da Troia e la tomba di Enea circondata da alberi: «Si tratta di un piccolo tumulo, intorno al quale sono stati posti file regolari di alberi, che vale la pena di vedere» (Ant. Rom. I, 64, 5)

Alba

Lavinium fu considerata anche il luogo delle origini del popolo romano: all’immagine di Roma nel momento della sua espansione e della crescita del suo potere era utile costruire una discendenza mitica da Enea, figlio di Venere, onorato per le sue virtù, per la capacità di assecondare gli dèi; di conseguenza si affermò anche la tradizione per la quale Romolo, il fondatore di Roma, aveva le sue origini, dopo quattro secoli, dalla medesima stirpe di Enea.

Secondo questa tradizione Ascanio Iulo, il figlio di Enea, aveva fondato Alba Longa, città posta presso l’attuale Albano, dando l’avvio a una dinastia, che serviva per colmare i quattrocento anni che separano le vicende di Enea (XII sec. a.C.) dalla fondazione di Roma (VIII se. a.C.), quando, dalla stessa stirpe, nacquero i gemelli Romolo e Remo, secondo la tradizione allattati da una lupa. Questi erano dunque i nipoti del re di Alba Longa. La madre era Rea Silvia e il padre il dio Marte. Romolo uccise Remo e poi fondò Roma nel 753 a.C. Lavinium diventava così la città sacra dei Romani, dove avevano sede i “sacri princìpi del popolo romano”.

Il Borgo sorge su una altura occupata nell’antichità dall’acropoli di Lavinium. In età imperiale vi sorge una domus, testimoniata da pavimenti in mosaico in bianco e nero (Borgo_1). Una civitas Pratica è ricordata per la prima volta in un documento del 1061, mentre nell’epoca successiva si parla di un castrum che fu di proprietà del Monastero di San Paolo fino al 1442. La Tenuta di Pratica di Mare, comprendente anche il Borgo, allora definito “Castello” (Borgo_2), divenne poi proprietà della famiglia Massimi e in seguito fu acquistata nel 1617 dai Borghese. Il principe Giovan Battista, nel tentativo di valorizzare il territorio con l’agricoltura, ristrutturò il villaggio nella forma che ancora oggi rimane, caratteristica per la sua pianta ortogonale e la sua unitarietà. Dalla metà dell’Ottocento la malaria, che devastava la campagna romana, causò lo spopolamento del borgo, finché Camillo Borghese dal 1880 si impegnò nell’opera di ricolonizzazione, restaurando il palazzo e intervenendo con una importante opera di riassetto della tenuta, dove fu impiantata una singolare vigna a pianta esagonale. Il Borgo e la tenuta rappresentano una preziosa area monumentale e agricola ancora intatta all’interno della zona degradata di Pomezia e Torvaianica.

Read more

F. Zevi (a cura di), Museo Archeologico dei Campi Flegrei. Catalogo generale. Cuma, Napoli 2008

C. Rescigno, “I templi della rocca e l’architettura sacra a Cuma tra età ellenistica e romana”, in M. Valenti (a cura di), Architettura del sacro in età romana: paesaggi, modelli, forme e comunicazione, Roma 2016, pp. 113-125

T. E. Cinquantaquattro, C. Rescigno, « Una suonatrice di lira e un guerriero. Due bronzetti dagli scavi sull’acropoli di Cuma », Mélanges de l’École française de Rome – Antiquité [En ligne], 129-1 | 2017, mis en ligne le 26 septembre 2017, consulté le 16 juin 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/mefra/4214 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/mefra.4214

INTRODUCTION

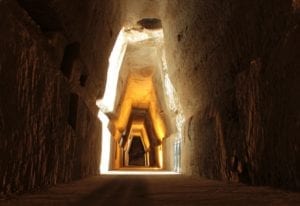

Aeneas arrives in Cuma to question the Sibyl. The prophetess, pervaded by the god Apollo, can predict the future and inform him of the vicissitudes that he will have to face, she makes him glimpse the future greatness of Rome and guides him in Hades. The doors of the underworld open at the lake of Averno, where Aeneas goes down to see his father Anchises. The entire book VI of the Aeneid is consecrated to the episode and numerous are the references to the sacred places of the city of Cuma: the temple of Apollo, the highest of the acropolis, built by none other than Daedalus fleeing from Crete, surrounded by the wood sacred to Artemis; the cave of the Sibyl, the doors of Hades.

Contacts

Map

Modulo di contatto

Donec leo sapien, porta sed nibh rutrum, bibendum posuere libero.